John Lewis Studio Art as Shown in the Smithsonian

:focal(878x841:879x842)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e2/3b/e23b578e-d0a6-4cc7-ba61-01b6d6c05cd5/npg_94_95-lewis-r.jpg)

Kidnapped, beaten and left to die, Edmonia Lewis, a talented creative person with both African and Native-American ancestry, refused to abandon her dreams. In the winter of 1862, a white mob had attacked her because of reports that she had poisoned two boyfriend Oberlin College students, drugging their wine with "Spanish Fly." Dilapidated and struggling to recover from serious injuries, she went to court and won an acquittal.

Though these details are apparently truthful, later on condign an internationally known sculptor, Lewis used threads of both truth and imagination to embroider her life story, artfully adding to her reputation equally a unique person and a sculptor who refused to be limited by the narrow expectations of her contemporaries.

Amongst the collections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum are several of Lewis' works, and her most pregnant piece of work, The Decease of Cleopatra, greets visitors who climb to the museum's 3rd floor in the Luce Foundation Center. Many of Lewis's works disappeared from the art globe, but her prototype of Cleopatra found its way back from obscurity later a decades-long sojourn that carried its ain strange story of fame and lost fortunes.

Lewis shattered expectations about what female and minority artists could achieve. "It was very much a man'southward world," says the museum'south curator Karen Lemmey. Lewis, she says, "actually broke through every obstacle, and at that place'due south still remarkably fiddling known near her. . . . It'south only recently that the identify and year of her expiry take come to light—1907 London."

The artist proved to be specially savvy virtually winning over supporters in the press and in the fine art earth by altering her life story to adjust her audition. "Everything that we know about her actually must be taken with a grain of salt, a pretty hefty grain of salt, considering in her own time, she was a chief of her own biography," says Lemmey. Lewis shifted her autobiographical tale to win support, but she did not welcome reactions of compassion or condescension.

"Some praise me considering I am a colored girl, and I don't want that kind of praise," she said. "I had rather yous would point out my defects, for that will teach me something."

Lewis'due south life was profoundly uncommon. Named Wildfire at nativity, she apparently had a partially Chippewa mother and a Haitian male parent. Lewis claimed her mother was full-blooded Chippewa, merely there is disagreement on this point. That parentage set her apart and added to her "exotic" epitome. Her begetter labored as a gentleman'south servant, while her mother made Native-American souvenirs for sale to tourists.

After both parents died when she was young, Lewis was reared by maternal aunts in upstate New York. She had a one-half-brother who traveled west during the Gold Rush and earned enough money to finance her education, a rare opportunity for a woman or a minority in the 19th century. She was welcomed at the progressive Oberlin College in 1859, only her time in that location was non easy. Even subsequently beingness cleared of poisoning charges, Lewis was unable to end her last term at Oberlin post-obit allegations that she had stolen paint, brushes and a picture frame. Despite dismissal of the theft charges, the college asked her to leave with no chance to complete her education and receive her degree.

She moved to Boston, again with fiscal assistance from her half-blood brother. There, she met several abolitionists, such as William Lloyd Garrison, who supported her work.

Dissimilar white male sculptors, she could not ground her work in the study of anatomy. Such classes traditionally were limited to white men: however, a few white women paid to get a background in the discipline. Lewis could non afford classes, so she engaged her craft without the training her peers possessed. Sculptor Edward Brackett acted as her mentor and helped her to set up her own studio.

Her first success equally an creative person came from sale of medallions she fabricated of clay and plaster. These sculpted portraits featured images of renowned abolitionists, including Garrison, John Brown and Wendell Phillips, an abet for Native-Americans. But her get-go existent financial success came in 1864, when she created a bust of Civil War Colonel Robert Shaw, a white officeholder who had allowable the 54th Massachusetts infantry equanimous of African-American soldiers. Shaw had been killed at the second battle of Fort Wagner, and contemptuous Confederate troops dumped the bodies of Shaw and his troops into a mass grave. Copies of the bust sold well enough to finance Lewis's move to Europe.

From Boston, she traveled to London, Paris and Florence before deciding to live and work in Rome in 1866. Fellow American sculptor Harriet Hosmer took Lewis nether her wing and tried to help her succeed. Sculptors of that fourth dimension traditionally paid Roman stone crafters to produce their works in marble, and this led to some questions about whether the true artists were the original sculptors or the rock crafters. Lewis, who often lacked the money to hire help, chiseled near of her own figures.

While she was in Rome, she created The Death of Cleopatra, her largest and almost powerful work. She poured more than than four years of her life into this sculpture. At times, she ran low on money to consummate the monolithic work, so she returned to the U.s., where she sold smaller pieces to earn the necessary cash. In 1876, she shipped the nearly 3,000-pound sculpture to Philadelphia so that the piece could be considered by the commission selecting works for the Centennial Exhibition, and she went there, too. She feared that the judges would refuse her piece of work, but to her great relief, the panel ordered its placement in Gallery G of Memorial Hall, apparently set aside for American artists. Guidebook citations of the piece of work noted that information technology was for auction.

"Some people were blown away past it. They thought it was a masterful marble sculpture," says Lemmey. Others disagreed, criticizing its graphic and agonizing image of the moment when Cleopatra killed herself. Ane artist, William J. Clark Jr. wrote in 1878 that "the effects of death are represented with such skill as to be absolutely repellent—and it is a question whether a statue of the ghastly characteristics of this one does not overstep the bounds of legitimate fine art." The moment when the asp's toxicant did its job was too graphic for some to run into.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5c/d4/5cd40945-f958-46fc-8d81-ad7289a9f4ec/199417.jpg)

Lewis showed the legendary queen of ancient Arab republic of egypt on her throne. The lifeless body with head tilting dorsum and arms splaying open portrays a vivid realism uncharacteristic of the late 19th century. Lewis showed the empowered Cleopatra "challenge her biography by committing suicide on her throne," says Lemmey. She believes Lewis portrayed Cleopatra "sealing her fate and having the concluding discussion on how she'll be recorded in history," an thought that may have appealed to Lewis.

Subsequently the Philadelphia exhibition ended, this Cleopatra began a life of her own and an odyssey that removed the sculpture from the art world for more than a century. She appeared in the Chicago Interstate Industrial Expo, and with no buyer in sight inside the art world, she journeyed into the realm of the mundane. Similar legendary wanderers before her, she faced many trials and an extended episode of mistaken identity every bit she was cast in multiple roles. Her first mission was to serve as the centerpiece of a Chicago saloon. And so, a racehorse possessor and gambler named "Blind John" Condon bought her to place on the racetrack grave of a well-loved horse named after the ancient leader. Like a notorious prisoner held upwardly to ridicule, the sculpture saturday right in forepart of the crowd at the Harlem Race Runway in Forest Park, a Chicago suburb. There, Cleopatra held courtroom while the work's surroundings morphed.

Over the years, the racetrack became a golf course, a Navy munitions site, and finally a majority postal service centre. In all kinds of weather, the royal Egyptian decayed as she served as little more than than an obstacle to whatever activity was occurring effectually information technology. Well-pregnant amateurs tried to improve her appearance. Boy Scouts applied a fresh glaze of paint to cover graffiti that marred its marble form. In the 1980s, she was handed over to the Woods Park Historical Society, and art historian Marilyn Richardson played a leading office in the endeavor to rescue her.

In the early 1990s, the historical order donated the sculpture to the Smithsonian, and a Chicago conservator was hired to return it to its original form based on a unmarried surviving photograph. Although the museum has no plans for further restoration, Lemmey hopes that digital photo projects at institutions effectually the world someday may unearth more images of the sculpture's original state.

Just every bit the sculpture's history is complicated and somewhat unclear, the artist herself remains a bit of a mystery. Known as ane of the first black professional sculptors, Lewis left behind some works, but many of her sculptures have disappeared. She had produced a variety of portrait busts that honored famous Americans, such equally Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, and Henry Wordsworth Longfellow.

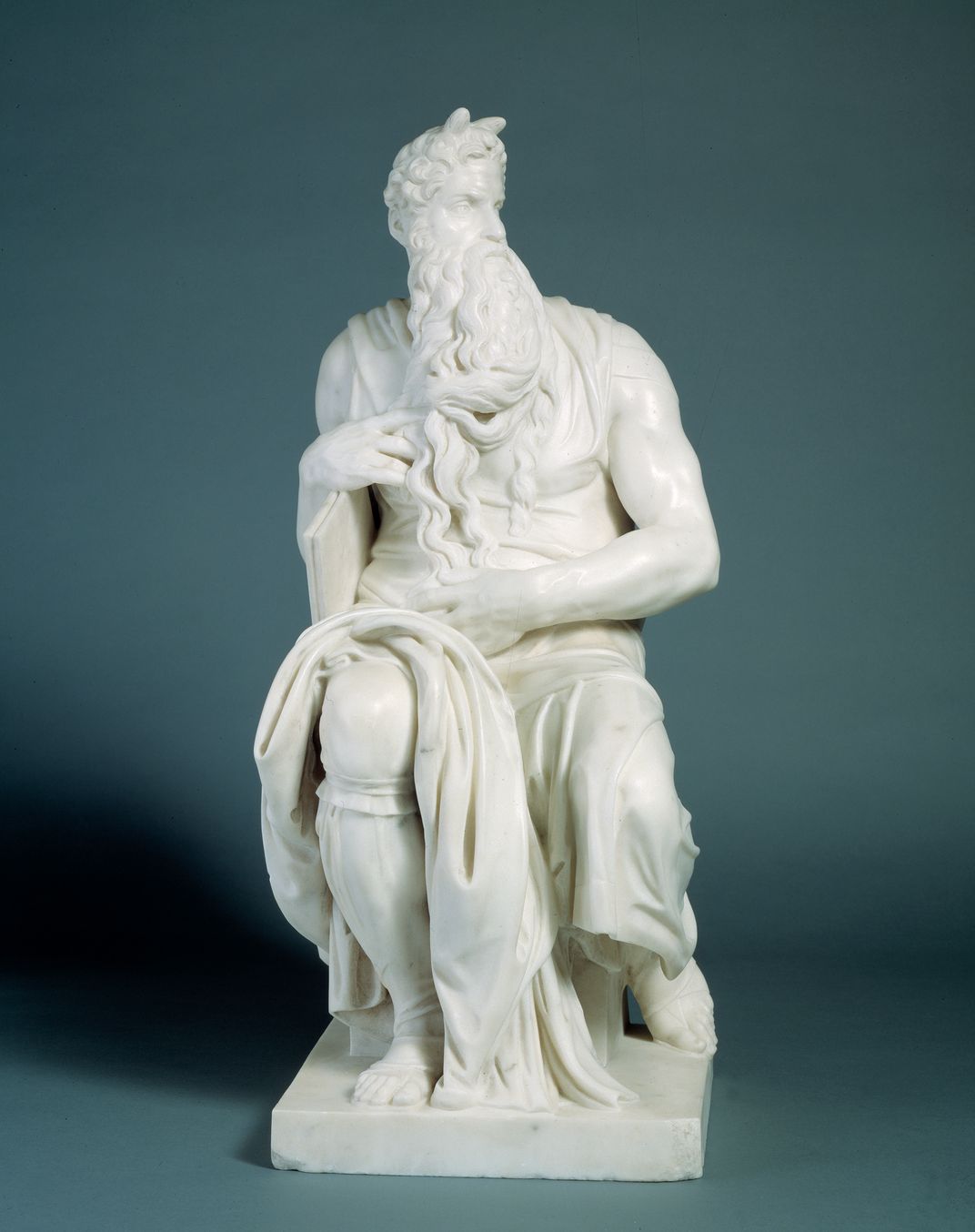

During her beginning year in Rome, she produced Old Arrow Maker, which represents a portion of the story of Longfellow'due south "The Song of Hiawatha"—a verse form that inspired several of her works. White artists typically characterized Native Americans every bit violent and uncivilized, but Lewis showed more respect for their civilisation. This sculpture also resides at the Smithsonian American Fine art Museum.

Her first major piece of work, Forever Free (Morn of Liberty), was completed a twelvemonth after her arrival in Rome. Information technology shows a black human standing and a black woman kneeling at the moment of emancipation. Some other work, Hagar, embodies the Old Testament Egyptian slave Hagar after being ejected from Abraham and Sarah's dwelling. Because Sarah had been unable to have children, she had insisted that Abraham impregnate her slave, so that Hagar's child could become Sarah'south. However, later on Hagar gave birth to Ishmael, Sarah delivered her own son Isaac, and she cast out Hagar and Ishmael. This portrayal of Hagar draws parallels to Africans held as slaves for centuries in the U.s.a.. Hagar is a role of the Smithsonian American Fine art Museum's collection.

While many of her works did not survive, some of Lewis'south pieces now tin can exist found at the Howard Academy Gallery of Art, Detroit Plant of Arts, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Baltimore Museum of Art. Lewis recently became the subject of a Google Doodle that pictures her working on The Death of Cleopatra. Also, the New York Times featured her on July 25, 2018 in its "Overlooked No More" series of obituaries written about women and minorities whose lives had been ignored past newspapers because of the cultural prejudice that revered white men.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/sculptor-edmonia-lewis-shattered-gender-race-expectations-19th-century-america-180972934/

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/11/20/112060b6-b4e0-4c8b-a4e6-77268189b65a/198395178.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f1/2e/f12efd8f-0718-4f70-ac11-1c0bc71042e5/1984156.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/35/47/3547e371-39b1-4fdd-88a2-51a1185fdcda/198395179.jpg)

0 Response to "John Lewis Studio Art as Shown in the Smithsonian"

Post a Comment